This is the first installment of our first guest article. Owing to the length of this original text we will publish parts until the complete version is online. I would like to thank Maitre A. Crown, who first published a shorter and modified version of this article at his website many years ago and I'd also like to thank Maestro F. Lurz, the author for making his original thesis available. Among his many achievements, Maestro Lurz served as Assistant Director of the Fencing Masters Training Program at San Jose State University and served on its board of examiners. This board certified many of the fencing masters that we have all worked with since. A common thread throughout the instruction of these contemporary masters of the Italian tradition is efficiency and effective swordplay. In this article Maestro Lurz provides historical and forensic evidence for the importance of these traits.

INTRODUCTION

The science of swordsmanship has come down to us from ages long ago, and the details of its earliest origins and much of its subsequent development are lost, along with countless other priceless treasures, among the dust and ashes of time's terrible passage. Consequently, one can only witness with the mind's eye that fateful moment in history when a club-wielding combatant first realized the unique property of a sharp stick and the advantage to which it could be employed. The moment became history; the stick became the weapon that changed the world.

Though not entirely lost, detailed information on the actual practice of swordsmanship is not altogether clear, owing to the passage of the era during which such weapons were used, the unreliability of personal anecdotes and biased accounts, unreported events, and the lack of any photographic means by which combat between swordsmen could be recorded. For the average individual, an understanding of what was involved in swordplay has been confused further by the motion picture industry. Scenes of cavaliers contemporaneously fighting dozens of adversaries while swinging from chandeliers, sliding down banisters, and leaping over furniture render a popular view of swordplay altogether inconsistent with the historical record. Although these performances may captivate a theater audience, such antics would doubtless be looked upon with considerable disdain by the fencing masters of the past.

“the duelist was guided by a basic principal of fencing understood by all serious fencers who faced the possibility of involvement in the duel: to hit without being hit”

While the science and art of fencing owes its origins and evolution to deadly combat, fencing now has been elevated (or perhaps demeaned) to the level of a sport. Modern innovations arising out of fencing's increasingly athletic character, plus modern technology and the conduct of fencing strictly as a game, have opened an ever widening gulf between fencing as an athletic exercise and fencing as a means of defending oneself in a duel. Motivated to excel in the sport for the honor and prestige such excellence confers, the modern competitive fencer seeks to win the touch, and with it the medals, awards, and other accolades which bear testimony to the victor's athletic prowess, within the limits of conventions which, while based on dueling practice, nevertheless allow for victory through means sometimes incompatible with serious swordplay. In contrast, the motive forces that drove the duelist to face an adversary with deadly weapons were many and complex, and the goals of the genuine swordsman were vastly different from those of today's sport fencer. By appearing on the terrain de combat, ready to fight, the duelist also won honor, respect and prestige. Out of grim necessity, however, he was compelled to pursue through his skill as a swordsman two important goals which are of little interest to today's fencing athlete: to place his adversary hors de combat, and to survive the ordeal intact. To accomplish these ends, the duelist was guided by a basic principal of fencing understood by all serious fencers who faced the possibility of involvement in the duel: to hit without being hit.

This work will explore the subject of dueling from the 15th through the 19th century via an examination of historical accounts of duels and through modern forensic medical literature pertaining to the subject of penetrating wounds, specifically those caused by sharp instruments. Its purpose is to gain an appreciation of the extraordinary durability of the human body and how difficult and dangerous it could be for a swordsman to eliminate an adversary. For the purposes of this discussion the weapons under consideration will include the rapier, the smallsword, and the sabre.

WEAPONRY

In order to gain an understanding of swordplay as it applied to the duel, it is necessary to become familiar with the weapons used and the types of injuries they had the potential to inflict. Throughout the medieval period, swords commonly consisted of a broad, straight, double-edged blade. The guard consisted of a cross bar, or quillion, at right angles to he blade, a grip of wood wound with leather or cord, and a heavy pommel fixed at the end. While the efficacy of the thrust over the cut had long been known, the medieval sword was nevertheless designed as a cutting instrument suited to use in warfare. By the 16th century, however, the increasing popularity of private, personal combat called for a lighter, more versatile weapon. Suited to thrusting as well as cutting actions, the rapier became the preferred weapon for duels fought against an adversary now on foot and unprotected by defensive armor.

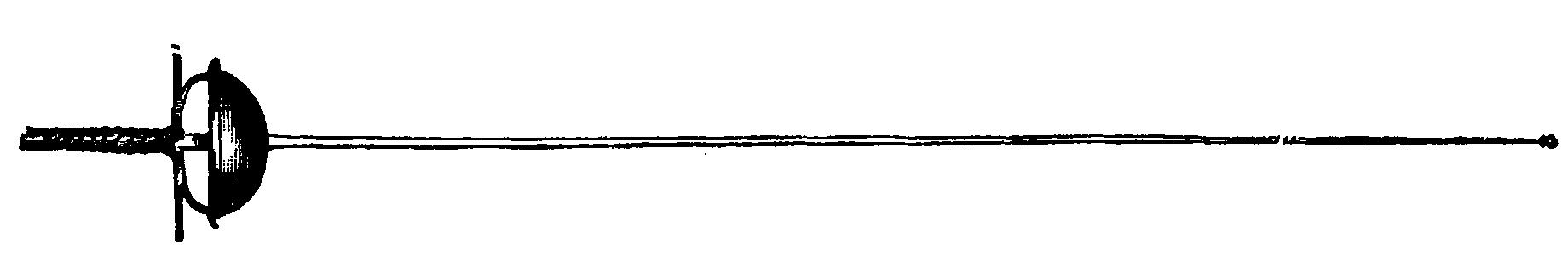

- The rapier, developed through the influence of the theories and techniques of swordplay being taught at that time by the masters of the Italian fencing schools, possessed a long, narrow blade ranging from 86 to as many as 150 centimeters in length. Double-edged and ending in a sharp point, these blades were designed to employ both thrusting and cutting actions. Rapier hilts were of a wide variety of types and styles, but generally consisted of quillions, a hemispherical cup or a series of rings to protect the hand, a knuckle guard, a grip and a pomme1. As time passed, improved fencing techniques for the rapier were developed, which in turn, called for changes in rapier design. As a result of this evolution, the weapon became shorter and lighter, and the guard became smaller.

- The final step in the evolution of the rapier produced the smallsword, which first appeared toward the end of the 17th century. The blade architecture of these weapons initially included designs that were elliptical, diamond, or even hexagonal in cross-section; but a grooved, triangular shape, producing a blade that was stiff, strong, and light, finally became the preferred design. Unlike the early rapier, the smallsword was used exclusively for thrusting. Consequently, the later, triangular blades frequently possessed either no sharp cutting edge, or retained it only partially, not for the purpose of delivering a cutting stroke, but to discourage an adversary from deflecting the blade with his unarmed hand or grasping it in an attempt to effect a manual disarmament.

- The first fencing treatise to make mention of the sabre was published in 1686. The weapon became known in western Europe through contact with Hungarian light horsemen who, in turn, learned of it through the Turks. The sabre was equipped with a grip, guard, knuckle bow and a pommel. The sabre blade was frequently curved, with a sharp edge extending from the guard to the point. The back side of the blade also possessed an edge which was sharp along its distal third. Although relatively heavy sabres were used extensively by the cavalry of all nations as a weapon of war, a lighter form weapon was also employed in dueling practice. The sabre was intended mainly for cutting, but like the rapier, it was also effective in thrusting.

next time, the Evolution of the Duel...